Smart Kids More Likely to Use Drugs

Original Post: Huffington Post by

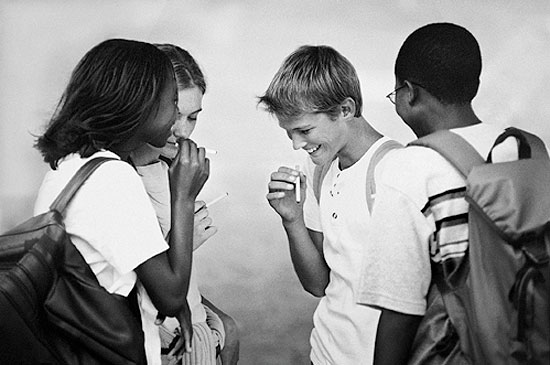

How’s this for peer pressure? Not only do the cool kids smoke pot, but it turns out the smart kids do, too.

We joke, of course. But a new study suggests that teens with high scores on academic exams were almost twice as likely as low-scoring peers to use cannabis persistently at ages 18 to 20. Smarter kids also were less likely than low scorers to smoke cigarettes, and more likely to drink.

Lest you consider this study permission to claim your youthful indiscretions as confirmation of genius, consider this: The researchers regard their findings as a warning against assuming that teens with poor academic performance are more likely to abuse substances than their peers. They also note that while high-achieving teens may eventually get into good universities and secure high-paying jobs, substance abuse can derail those promising futures. For instance, some evidence suggests that marijuana can have a harmful effect on developing brains, and alcohol use among minors is linked to a higher risk of fatal car collisions, accidental injuries, alcohol poisoning, and suicide.

“Reducing harmful substance use in this age group is important, no matter the level of academic ability, given the immediate risks to health and the longer term consequences,” researchers James Williams and Gareth Hagger-Johnson write in their article, published in the journal BMJ Open.

The relationship between substance use and academic achievement

Williams and Hagger-Johnson, from the University College London Medical School, got data from about 6,000 representative participants across England and sorted them into three groups based on results of a nationwide test all English students take around age 11.

They tracked these students over the years with surveys that included questions about cigarette, alcohol and cannabis use, zooming in on early adolescence ― ages 13 to 17 ― and late adolescence ― ages 18 to 20.

They found that the high-scoring students were 62 percent less likely than low scorers to smoke cigarettes in early adolescence, but were 25 percent more likely to drink occasionally (not every year) in early adolescence, compared with the low scorers. Their chances of drinking persistently (every year) was more than double in late adolescence.

Finally, the high-scoring kids were also 50 percent more likely to use pot occasionally, and 91 percent more likely to use pot persistently, from ages 18 onward. Compared with low scorers, the medium-scoring kids had a 37-percent higher likelihood for occasional use, and 81 percent for persistent use.

The same was true for alcohol. High-scoring students were more than twice as likely to drink alcohol, compared with low-scoring peers in late adolescence, while medium-scoring teens were 56 percent more likely to drink, compared with low scorers.

Why do more intelligent teens experiment with drugs and alcohol?

Do smarter teens know something other kids don’t about illicit drugs? Why are smarter teens more drawn to cannabis over cigarettes? This kind of study doesn’t measure what causes these kinds of associations, and it can’t definitively say why smarter teens tend to have higher rates of cannabis and alcohol use than others.

Potential explanations range from the possibility that smarter kids may be more open to new experiences, be more accepted by older peers who have access to these substances, or simply may be more honest when filling out self-reported surveys, the researchers said. Parents could have something to do with the association, as intelligent and wealthy parents tend to drink more alcohol and shun cigarettes.

The new findings seem to line up with past research on adults, who are also more likely to use cannabis and drink more if they score highly on intelligence tests.

Some of the study’s limitations include the fact that there was no data on cigarette smoking after age 16, and that the teens weren’t able to regularly use cannabis until they reached age 18. The researchers also couldn’t collect data on the amount of alcohol and cannabis teens consumed. All of those shortcomings point to the need for more research.